Local Wellness Funds

What is a local wellness fund?

A locally controlled pool of funds created to support community well-being and clinical prevention efforts that improve population health outcomes and reduce health inequities. Sources of funding may be public and/or private.

Local wellness funds are a promising approach to sustainably assemble resources to finance community prevention efforts and address other drivers of health outside of the health care delivery system, like housing, education, poverty, food availability, and access to safe recreational areas. Addressing these upstream drivers of well-being provides an opportunity for involvement of a broader group of stakeholders to jointly address health outcomes. Bringing together the right people is an important first step. But communities must also figure out how to fund these initiatives targeting the upstream drivers of health and wellness. Experts increasingly see the ability to tap into and coordinate various funding streams as a key strategy for financial sustainability of community health improvement efforts.¹

Communities around the nation are thinking innovatively about aligning streams of resources to sustainably support initiatives of shared interest and importance. They are blending and braiding resources from a mix of:

- Philanthropic grants

- Revenue from tax or other state-funded sources

- Hospital community benefits dollars

- Contributions from businesses, insurers, and community banks

Potential population-level benefits from these funds may be seen across sectors.

At the national level, the Prevention and Public Health Fund was established under the Affordable Care Act in 2010 to provide expanded and sustained national investments in prevention and public health, to improve health outcomes, and to enhance health care quality. Specific uses to date included:

- Community and clinical prevention initiatives

- Research, surveillance, and tracking

- Public health infrastructure

- Immunizations and screenings

- Tobacco prevention

- Public health workforce and training

Over time, the sustainability of the fund, due to waning appropriations, has become increasingly fragile.²

The Massachusetts Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund was one of the nation’s largest, financed with $60 million over a four-year period, through a small assessment fee on health insurers and acute care hospitals. While much of the evaluation of the effort suggested population health improvement gains across the state,³ appropriations to the fund dried up in 2017. Other states have been experimenting with the concept to varying degrees, including Minnesota, Oklahoma, California, and Hawaii.⁴

Local or regional funds hold the promise of a mechanism that might potentially be more sustainable over time. This is because, as Kindig points out, “they are less expensive, more politically feasible, and present a path to longer-term solutions than counting on unlikely new federal or state appropriations. … They serve as stable and permanently staffed governance bodies, multi-sectoral coordinating entities whose public- and private-sector leaders meet regularly, establish local goals and priorities, and identify resources for substantial and continuous investment in improving overall health and health equity.”⁵

The Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC) at Georgia State University initially conceived the sources, uses, and structure framework as way to examine fund development. As communities move through the implementation process, this framework remains useful, as many collaboratives will re-evaluate potential sources of funding, how and where to allocate fund resources, and the appropriateness of accountability structures over the lifespan of their fund.

Early Learnings Show:

Sources:

Medicaid is a common source of funding, particularly in states with Medicaid expansion. Funds are interested in better understanding the process of incorporating tax revenue.

Uses:

Funds must balance a variety of factors in deciding what to prioritize. These considerations include local needs, donor priorities, emerging needs, and community input. Good data are needed to measure the success of the fund’s uses and demonstrate return on investment.

Structure:

Multisector leadership is perceived to be a driver of fund success. Investment in capacity building and cross-sector collaboration may increase resiliency.

Cross-cutting Factors:

Funds need to have the structure and capacity to manage funds and the ability to convey that capacity to donors. Further development is needed in the areas of authentic community engagement, measurement of impact, and incorporation of equity in fund processes

The Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC) at Georgia State University initially conceived the sources, uses, and structure framework as way to examine fund development. As communities move through the implementation process, this framework remains useful, as many collaboratives will re-evaluate potential sources of funding, how and where to allocate fund resources, and the appropriateness of accountability structures over the lifespan of their fund.

Sources

Uses

Structure

Early Learnings Show:

Sources:

Medicaid is a common source of funding, particularly in states with Medicaid expansion. Funds are interested in better understanding the process of incorporating tax revenue.

Uses:

Funds must balance a variety of factors in deciding what to prioritize. These considerations include local needs, donor priorities, emerging needs, and community input. Good data are needed to measure the success of the fund’s uses and demonstrate return on investment.

Structure:

Multisector leadership is perceived to be a driver of fund success. Investment in capacity building and cross-sector collaboration may increase resiliency.

Cross-cutting Factors:

Funds need to have the structure and capacity to manage funds and the ability to convey that capacity to donors. Further development is needed in the areas of authentic community engagement, measurement of impact, and incorporation of equity in fund processes.

The Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC) at Georgia State University initially conceived the sources, uses, and structure framework as way to examine fund development. As communities move through the implementation process, this framework remains useful, as many collaboratives will re-evaluate potential sources of funding, how and where to allocate fund resources, and the appropriateness of accountability structures over the lifespan of their fund.

Sources

Uses

Structure

Early Learnings Show:

Sources:

Medicaid is a common source of funding, particularly in states with Medicaid expansion. Funds are interested in better understanding the process of incorporating tax revenue.

Uses:

Funds must balance a variety of factors in deciding what to prioritize. These considerations include local needs, donor priorities, emerging needs, and community input. Good data are needed to measure the success of the fund’s uses and demonstrate return on investment.

Structure:

Multisector leadership is perceived to be a driver of fund success. Investment in capacity building and cross-sector collaboration may increase resiliency.

Cross-cutting Factors:

Funds need to have the structure and capacity to manage funds and the ability to convey that capacity to donors. Further development is needed in the areas of authentic community engagement, measurement of impact, and incorporation of equity in fund processes.

Local Wellness Funds Framework

The Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC) at Georgia State University initially conceived the sources, uses, and structure framework as way to examine fund development. As communities move through the implementation process, this framework remains useful, as many collaboratives will re-evaluate potential sources of funding, how and where to allocate fund resources, and the appropriateness of accountability structures over the lifespan of their fund.

Sources

Where does the money come from?

Uses

What will the funds be used for?

Structure

How will these funds be managed, administered, and stewarded?

Development Stage Conceptualizing Developing Implementing Geography Population Size

Primary Contributors Number of sources Public or private Funding sectors Types of pooling Amount in the fund

Upstream versus downstream Single versus multi-focus Focus area(s) Special populations Outcome measures

Backbone functions Partnership Number Sectors represented Agreements Administrative model Third-party finance manager

The Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC), with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is working to understand and advance the practice of establishing local wellness funds as a means to sustainably fund population health improvement efforts across the country. An increasing number of multisectoral collaboratives are not only developing these funds through local action but are doing so in context-appropriate ways.

A 12-site cohort was established, with the overarching strategy of harnessing learnings from these sites, which are in varying stages of development and implementation. Below is a listing of the sites and the funds developed. Please visit their individual websites to learn more about their local wellness funds.

Better Health Together: Community Resilience Fund

Elevate Health: OnePierce Community Resilience Fund

Georgia Organics: Georgia Food Oasis and The Farmer Fund

Health Collaborative: Community Fund

Imperial County Local Health Authority: Wellness Fund

Jackson Collaborative Network – Henry Ford Allegiance Health

Local Initiatives Support Corp.: ProMedica-LISC Health Impact Fund

NEK Prosper: Healthy Cents Fund and NEK Prosperity Fund

Scattergood Foundation: Community Fund for Immigrant Wellness

St. Louis County Housing Resources Commission: Affordable Housing Trust Fund

Western Idaho Health Collaborative

Yamhill Community Care Organization: Community Prevention and Wellness Fund

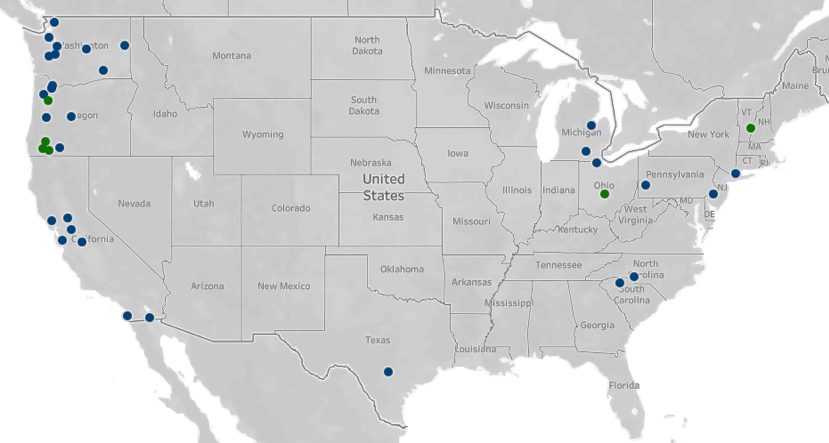

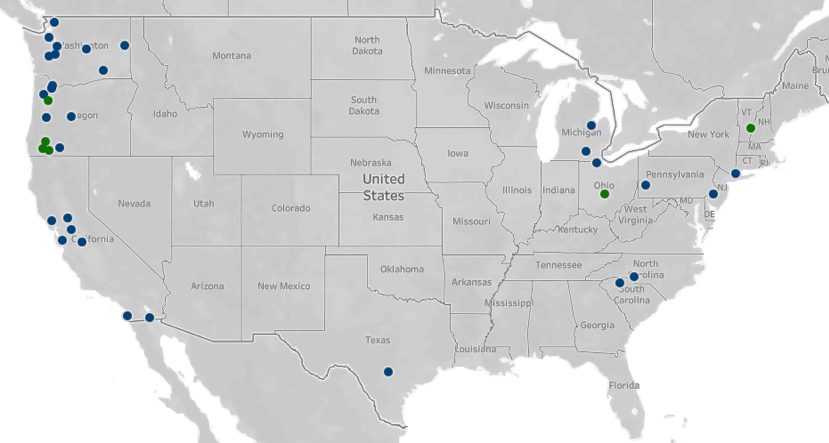

When local wellness funds: Advancing the Practice launched in April 2019, GHPC designed and implemented a discovery phase to document where wellness fund activity is occurring nationally. Given the great diversity of fund names and uses, it was difficult to build a comprehensive list from public records. While work to surface local wellness funds is continuing, the preliminary search in November 2019 found 38 domestic efforts to establish local wellness funds. Among the 38 domestic efforts identified:

- More than two-thirds of local wellness funds (25) are located on the West Coast.

- The remaining local wellness funds are scattered nationally in the Southwest (2), Midwest (5), Northeast (4), and Southeast (2)

GHPC confirmed 13 active local wellness funds and seven ongoing efforts to establish a fund.⁶

In August of 2020 the scan was updated. The map below includes identified active local wellness funds, including those participating in the cohort. During COVID-19, efforts across the country to establish new local wellness funds were slowed as communities worked to respond to the pandemic.

This initiative was born out of the Bridging for Health: Improving Community Health Through Innovations in Financing, during which all seven collaboratives pursued local wellness funds as an overarching vehicle to assemble resources to improve population health.⁷ At the last date of follow-up, the seven sites collectively accumulated more than $3 million to support population health.

With support from the philanthropic community and in some cases as a result of state and federal policy initiatives (e.g., Accountable Communities of Health),⁸ more health-oriented community collaboratives across the country are making efforts to adapt the design principles of wellness funds to impact local jurisdictions. By some reports, the uptake has been slow, but these organizations and others are continuing to examine and experiment with approaches to financing that go beyond periodic grant funding and seek to impact upstream health.

- More than two-thirds of local wellness funds (25) are located on the West Coast.

- The remaining local wellness funds are scattered nationally in the Southwest (2), Midwest (5), Northeast (4), and Southeast (2)

- Trust for America’s Health. (2016). Sustainable Funding for Healthy Communities Local Health Trusts: Structures to Support Local Coordination of Funds Accessed at https://www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Local-Health-Trusts-Convening-Summary.pdf

- Haberkorn, J. (2012). The Prevention and Public Health Fund. Health Affairs, Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20120223.98342/

- Zotter, J. (2017). Joining forces: Adding public health value to healthcare reform. The Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund, Retrieved from https://masspublichealth.org/index.php/2017-annual-report/

- Cohen, L. Mikkelsen, L., Aboelta, M., et al. (2015). Sustainable Investments in Health: Prevention and Wellness Funds — A Primer on Their Structure, Function and Potential. Prevention Institute. Retrieved from https://www.preventioninstitute.org/publications/sustainable-investments-health-prevention-and-wellnessfunds

- Kindig, D. (2016). To launch and sustain local health outcome trusts. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved from healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20160210.053102/full

- Georgia Health Policy Center. (2019, November). Advancing the Practice: Discovery Phase. Retrieved from https://ghpc.gsu.edu/download/advancing-the-practice-discovery-phase/?wpdmdl=4753310&refresh=6142a512e67181631757586

- Minyard, K., Heberlein, E., Parker, C., et al. (2019). Bridging for Health: Improving Community Health Through Innovations in Financing. Georgia Health Policy Center, Atlanta, GA. Retrieved from ghpc.gsu.edu/download/bridging-for-health-book

- Heinrich, J., Levi, J., Hughes, D., Mittmann, H., (2020). Wellness funds: Flexible funding to Advance the Health of Communities). Funders Forum on Accountable Health, Retrieved from https://accountablehealth.gwu.edu/sites/accountablehealth.gwu.edu/files/Wellness%20Fund%20Brief%20-%20Final.pdf